You are viewing documentation for Kubernetes version: v1.21

Kubernetes v1.21 documentation is no longer actively maintained. The version you are currently viewing is a static snapshot. For up-to-date documentation, see the latest version.

Gardener - The Kubernetes Botanist

Authors: Rafael Franzke (SAP), Vasu Chandrasekhara (SAP)

Today, Kubernetes is the natural choice for running software in the Cloud. More and more developers and corporations are in the process of containerizing their applications, and many of them are adopting Kubernetes for automated deployments of their Cloud Native workloads.

There are many Open Source tools which help in creating and updating single Kubernetes clusters. However, the more clusters you need the harder it becomes to operate, monitor, manage, and keep all of them alive and up-to-date.

And that is exactly what project "Gardener" focuses on. It is not just another provisioning tool, but it is rather designed to manage Kubernetes clusters as a service. It provides Kubernetes-conformant clusters on various cloud providers and the ability to maintain hundreds or thousands of them at scale. At SAP, we face this heterogeneous multi-cloud & on-premise challenge not only in our own platform, but also encounter the same demand at all our larger and smaller customers implementing Kubernetes & Cloud Native.

Inspired by the possibilities of Kubernetes and the ability to self-host, the foundation of Gardener is Kubernetes itself. While self-hosting, as in, to run Kubernetes components inside Kubernetes is a popular topic in the community, we apply a special pattern catering to the needs of operating a huge number of clusters with minimal total cost of ownership. We take an initial Kubernetes cluster (called "seed" cluster) and seed the control plane components (such as the API server, scheduler, controller-manager, etcd and others) of an end-user cluster as simple Kubernetes pods. In essence, the focus of the seed cluster is to deliver a robust Control-Plane-as-a-Service at scale. Following our botanical terminology, the end-user clusters when ready to sprout are called "shoot" clusters. Considering network latency and other fault scenarios, we recommend a seed cluster per cloud provider and region to host the control planes of the many shoot clusters.

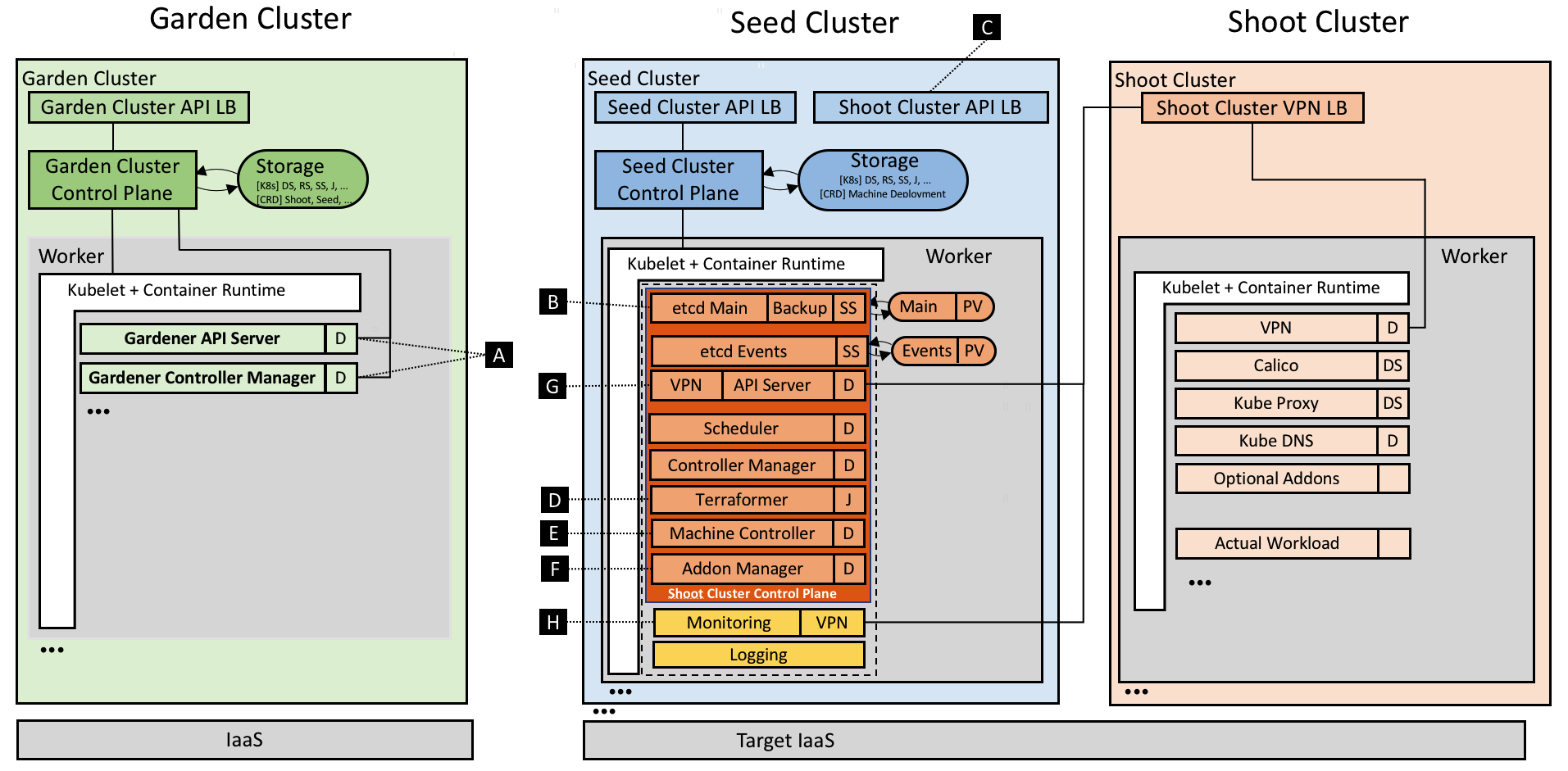

Overall, this concept of reusing Kubernetes primitives already simplifies deployment, management, scaling & patching/updating of the control plane. Since it builds upon highly available initial seed clusters, we can evade multiple quorum number of master node requirements for shoot cluster control planes and reduce waste/costs. Furthermore, the actual shoot cluster consists only of worker nodes for which full administrative access to the respective owners could be granted, thereby structuring a necessary separation of concerns to deliver a higher level of SLO. The architectural role & operational ownerships are thus defined as following (cf. Figure 1):

- Kubernetes as a Service provider owns, operates, and manages the garden and the seed clusters. They represent parts of the required landscape/infrastructure.

- The control planes of the shoot clusters are run in the seed and, consequently, within the separate security domain of the service provider.

- The shoot clusters' machines are run under the ownership of and in the cloud provider account and the environment of the customer, but still managed by the Gardener.

- For on-premise or private cloud scenarios the delegation of ownership & management of the seed clusters (and the IaaS) is feasible.

Figure 1 Technical Gardener landscape with components.

The Gardener is developed as an aggregated API server and comes with a bundled set of controllers. It runs inside another dedicated Kubernetes cluster (called "garden" cluster) and it extends the Kubernetes API with custom resources. Most prominently, the Shoot resource allows a description of the entire configuration of a user's Kubernetes cluster in a declarative way. Corresponding controllers will, just like native Kubernetes controllers, watch these resources and bring the world's actual state to the desired state (resulting in create, reconcile, update, upgrade, or delete operations.) The following example manifest shows what needs to be specified:

apiVersion: garden.sapcloud.io/v1beta1

kind: Shoot

metadata:

name: dev-eu1

namespace: team-a

spec:

cloud:

profile: aws

region: us-east-1

secretBindingRef:

name: team-a-aws-account-credentials

aws:

machineImage:

ami: ami-34237c4d

name: CoreOS

networks:

vpc:

cidr: 10.250.0.0/16

...

workers:

- name: cpu-pool

machineType: m4.xlarge

volumeType: gp2

volumeSize: 20Gi

autoScalerMin: 2

autoScalerMax: 5

dns:

provider: aws-route53

domain: dev-eu1.team-a.example.com

kubernetes:

version: 1.10.2

backup:

...

maintenance:

...

addons:

cluster-autoscaler:

enabled: true

...

Once sent to the garden cluster, Gardener will pick it up and provision the actual shoot. What is not shown above is that each action will enrich the Shoot's status field indicating whether an operation is currently running and recording the last error (if there was any) and the health of the involved components. Users are able to configure and monitor their cluster's state in true Kubernetes style. Our users have even written their own custom controllers watching & mutating these Shoot resources.

Technical deep dive

The Gardener implements a Kubernetes inception approach; thus, it leverages Kubernetes capabilities to perform its operations. It provides a couple of controllers (cf. [A]) watching Shoot resources whereas the main controller is responsible for the standard operations like create, update, and delete. Another controller named "shoot care" is performing regular health checks and garbage collections, while a third's ("shoot maintenance") tasks are to cover actions like updating the shoot's machine image to the latest available version.

For every shoot, Gardener creates a dedicated Namespace in the seed with appropriate security policies and within it pre-creates the later required certificates managed as Secrets.

etcd

The backing data store etcd (cf. [B]) of a Kubernetes cluster is deployed as a StatefulSet with one replica and a PersistentVolume(Claim). Embracing best practices, we run another etcd shard-instance to store Events of a shoot. Anyway, the main etcd pod is enhanced with a sidecar validating the data at rest and taking regular snapshots which are then efficiently backed up to an object store. In case etcd's data is lost or corrupt, the sidecar restores it from the latest available snapshot. We plan to develop incremental/continuous backups to avoid discrepancies (in case of a recovery) between a restored etcd state and the actual state [1].

Kubernetes control plane

As already mentioned above, we have put the other Kubernetes control plane components into native Deployments and run them with the rolling update strategy. By doing so, we can not only leverage the existing deployment and update capabilities of Kubernetes, but also its monitoring and liveliness proficiencies. While the control plane itself uses in-cluster communication, the API Servers' Service is exposed via a load balancer for external communication (cf. [C]). In order to uniformly generate the deployment manifests (mainly depending on both the Kubernetes version and cloud provider), we decided to utilize Helm charts whereas Gardener leverages only Tillers rendering capabilities, but deploys the resulting manifests directly without running Tiller at all [2].

Infrastructure preparation

One of the first requirements when creating a cluster is a well-prepared infrastructure on the cloud provider side including networks and security groups. In our current provider specific in-tree implementation of Gardener (called the "Botanist"), we employ Terraform to accomplish this task. Terraform provides nice abstractions for the major cloud providers and implements capabilities like parallelism, retry mechanisms, dependency graphs, idempotency, and more. However, we found that Terraform is challenging when it comes to error handling and it does not provide a technical interface to extract the root cause of an error. Currently, Gardener generates a Terraform script based on the shoot specification and stores it inside a ConfigMap in the respective namespace of the seed cluster. The Terraformer component then runs as a Job (cf. [D]), executes the mounted Terraform configuration, and writes the produced state back into another ConfigMap. Using the Job primitive in this manner helps to inherit its retry logic and achieve fault tolerance against temporary connectivity issues or resource constraints. Moreover, Gardener only needs to access the Kubernetes API of the seed cluster to submit the Job for the underlying IaaS. This design is important for private cloud scenarios in which typically the IaaS API is not exposed publicly.

Machine controller manager

What is required next are the nodes to which the actual workload of a cluster is to be scheduled. However, Kubernetes offers no primitives to request nodes forcing a cluster administrator to use external mechanisms. The considerations include the full lifecycle, beginning with initial provisioning and continuing with providing security fixes, and performing health checks and rolling updates. While we started with instantiating static machines or utilizing instance templates of the cloud providers to create the worker nodes, we concluded (also from our previous production experience with running a cloud platform) that this approach requires extensive effort. During discussions at KubeCon 2017, we recognized that the best way, of course, to manage cluster nodes is to again apply core Kubernetes concepts and to teach the system to self-manage the nodes/machines it runs. For that purpose, we developed the machine controller manager (cf. [E]) which extends Kubernetes with MachineDeployment, MachineClass, MachineSet & Machine resources and enables declarative management of (virtual) machines from within the Kubernetes context just like Deployments, ReplicaSets & Pods. We reused code from existing Kubernetes controllers and just needed to abstract a few IaaS/cloud provider specific methods for creating, deleting, and listing machines in dedicated drivers. When comparing Pods and Machines a subtle difference becomes evident: creating virtual machines directly results in costs, and if something unforeseen happens, these costs can increase very quickly. To safeguard against such rampage, the machine controller manager comes with a safety controller that terminates orphaned machines and freezes the rollout of MachineDeployments and MachineSets beyond certain thresholds and time-outs. Furthermore, we leverage the existing official cluster-autoscaler already including the complex logic of determining which node pool to scale out or down. Since its cloud provider interface is well-designed, we enabled the autoscaler to directly modify the number of replicas in the respective MachineDeployment resource when triggering to scale out or down.

Addons

Besides providing a properly setup control plane, every Kubernetes cluster requires a few system components to work. Usually, that's the kube-proxy, an overlay network, a cluster DNS, and an ingress controller. Apart from that, Gardener allows to order optional add-ons configurable by the user (in the shoot resource definition), e.g. Heapster, the Kubernetes Dashboard, or Cert-Manager. Again, the Gardener renders the manifests for all these components via Helm charts (partly adapted and curated from the upstream charts repository). However, these resources are managed in the shoot cluster and can thus be tweaked by users with full administrative access. Hence, Gardener ensures that these deployed resources always match the computed/desired configuration by utilizing an existing watch dog, the kube-addon-manager (cf. [F]).

Network air gap

While the control plane of a shoot cluster runs in a seed managed & supplied by your friendly platform-provider, the worker nodes are typically provisioned in a separate cloud provider (billing) account of the user. Typically, these worker nodes are placed into private networks [3] to which the API Server in the seed control plane establishes direct communication, using a simple VPN solution based on ssh (cf. [G]). We have recently migrated the SSH-based implementation to an OpenVPN-based implementation which significantly increased the network bandwidth.

Monitoring & Logging

Monitoring, alerting, and logging are crucial to supervise clusters and keep them healthy so as to avoid outages and other issues. Prometheus has become the most used monitoring system in the Kubernetes domain. Therefore, we deploy a central Prometheus instance into the garden namespace of every seed. It collects metrics from all the seed's kubelets including those for all pods running in the seed cluster. In addition, next to every control plane a dedicated tenant Prometheus instance is provisioned for the shoot itself (cf. [H]). It gathers metrics for its own control plane as well as for the pods running on the shoot's worker nodes. The former is done by fetching data from the central Prometheus' federation endpoint and filtering for relevant control plane pods of the particular shoot. Other than that, Gardener deploys two kube-state-metrics instances, one responsible for the control plane and one for the workload, exposing cluster-level metrics to enrich the data. The node exporter provides more detailed node statistics. A dedicated tenant Grafana dashboard displays the analytics and insights via lucid dashboards. We also defined alerting rules for critical events and employed the AlertManager to send emails to operators and support teams in case any alert is fired.

[1] This is also the reason for not supporting point-in-time recovery. There is no reliable infrastructure reconciliation implemented in Kubernetes so far. Thus, restoring from an old backup without refreshing the actual workload and state of the concerned cluster would generally not be of much help.

[2] The most relevant criteria for this decision was that Tiller requires a port-forward connection for communication which we experienced to be too unstable and error-prone for our automated use case. Nevertheless, we are looking forward to Helm v3 hopefully interacting with Tiller using CustomResourceDefinitions.

[3] Gardener offers to either create & prepare these networks with the Terraformer or it can be instructed to reuse pre-existing networks.

Usability and Interaction

Despite requiring only the familiar kubectl command line tool for managing all of Gardener, we provide a central dashboard for comfortable interaction. It enables users to easily keep track of their clusters' health, and operators to monitor, debug, and analyze the clusters they are responsible for. Shoots are grouped into logical projects in which teams managing a set of clusters can collaborate and even track issues via an integrated ticket system (e.g. GitHub Issues). Moreover, the dashboard helps users to add & manage their infrastructure account secrets and to view the most relevant data of all their shoot clusters in one place while being independent from the cloud provider they are deployed to.

Figure 2 Animated Gardener dashboard.

More focused on the duties of developers and operators, the Gardener command line client gardenctl simplifies administrative tasks by introducing easy higher-level abstractions with simple commands that help condense and multiplex information & actions from/to large amounts of seed and shoot clusters.

$ gardenctl ls shoots

projects:

- project: team-a

shoots:

- dev-eu1

- prod-eu1

$ gardenctl target shoot prod-eu1

[prod-eu1]

$ gardenctl show prometheus

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE IP NODE

prometheus-0 3/3 Running 0 106d 10.241.241.42 ip-10-240-7-72.eu-central-1.compute.internal

URL: https://user:password@p.prod-eu1.team-a.seed.aws-eu1.example.com

Outlook and future plans

The Gardener is already capable of managing Kubernetes clusters on AWS, Azure, GCP, OpenStack [4]. Actually, due to the fact that it relies only on Kubernetes primitives, it nicely connects to private cloud or on-premise requirements. The only difference from Gardener's point of view would be the quality and scalability of the underlying infrastructure - the lingua franca of Kubernetes ensures strong portability guarantees for our approach.

Nevertheless, there are still challenges ahead. We are probing a possibility to include an option to create a federation control plane delegating to multiple shoot clusters in this Open Source project. In the previous sections we have not explained how to bootstrap the garden and the seed clusters themselves. You could indeed use any production ready cluster provisioning tool or the cloud providers' Kubernetes as a Service offering. We have built an uniform tool called Kubify based on Terraform and reused many of the mentioned Gardener components. We envision the required Kubernetes infrastructure to be able to be spawned in its entirety by an initial bootstrap Gardener and are already discussing how we could achieve that.

Another important topic we are focusing on is disaster recovery. When a seed cluster fails, the user's static workload will continue to operate. However, administrating the cluster won't be possible anymore. We are considering to move control planes of the shoots hit by a disaster to another seed. Conceptually, this approach is feasible and we already have the required components in place to implement that, e.g. automated etcd backup and restore. The contributors for this project not only have a mandate for developing Gardener for production, but most of us even run it in true DevOps mode as well. We completely trust the Kubernetes concepts and are committed to follow the "eat your own dog food" approach.

In order to enable a more independent evolution of the Botanists, which contain the infrastructure provider specific parts of the implementation, we plan to describe well-defined interfaces and factor out the Botanists into their own components. This is similar to what Kubernetes is currently doing with the cloud-controller-manager. Currently, all the cloud specifics are part of the core Gardener repository presenting a soft barrier to extending or supporting new cloud providers.

When taking a look at how the shoots are actually provisioned, we need to gain more experience on how really large clusters with thousands of nodes and pods (or more) behave. Potentially, we will have to deploy e.g. the API server and other components in a scaled-out fashion for large clusters to spread the load. Fortunately, horizontal pod autoscaling based on custom metrics from Prometheus will make this relatively easy with our setup. Additionally, the feedback from teams who run production workloads on our clusters, is that Gardener should support with prearranged Kubernetes QoS. Needless to say, our aspiration is going to be the integration and contribution to the vision of Kubernetes Autopilot.

[4] Prototypes already validated CTyun & Aliyun.

Gardener is open source

The Gardener project is developed as Open Source and hosted on GitHub: https://github.com/gardener

SAP is working on Gardener since mid 2017 and is focused on building up a project that can easily be evolved and extended. Consequently, we are now looking for further partners and contributors to the project. As outlined above, we completely rely on Kubernetes primitives, add-ons, and specifications and adapt its innovative Cloud Native approach. We are looking forward to aligning with and contributing to the Kubernetes community. In fact, we envision contributing the complete project to the CNCF.

At the moment, an important focus on collaboration with the community is the Cluster API working group within the SIG Cluster Lifecycle founded a few months ago. Its primary goal is the definition of a portable API representing a Kubernetes cluster. That includes the configuration of control planes and the underlying infrastructure. The overlap of what we have already in place with Shoot and Machine resources compared to what the community is working on is striking. Hence, we joined this working group and are actively participating in their regular meetings, trying to contribute back our learnings from production. Selfishly, it is also in our interest to shape a robust API.

If you see the potential of the Gardener project then please learn more about it on GitHub and help us make Gardener even better by asking questions, engaging in discussions, and by contributing code. Also, try out our quick start setup.

We are looking forward to seeing you there!